By Haris Gazdar and Hussain Bux Mallah

February 19th, 2024

What explains low turnouts in competitive elections in Pakistan? This blog offers an answer using the prism of social exclusion. Study based on research in south Punjab and north Sindh. Debts to Wilder, Cheema, Khan Mohmand, Javid and many others.

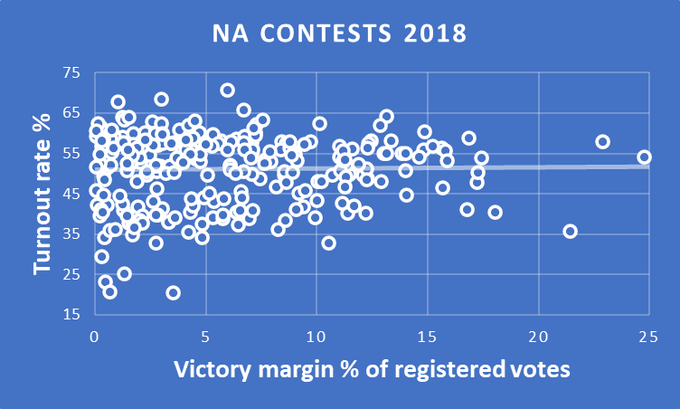

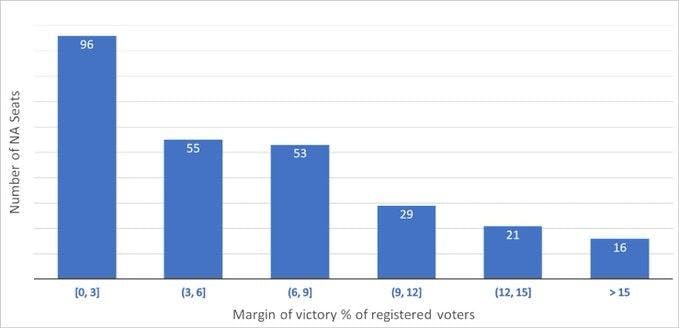

Elections in Pakistan are competitive. In 2018 the margin between the winner and runner was under 3% of registered voters on 96 out of 270 seats. The winning margin was under 6% in 151 seats. By contrast, non-voters averaged 49% of registered voters.

Why is the turnout rate low? Candidates and parties need not convert voters of rivals. Only flip a small proportion of non-voters into their voters to win. Graph plots NA seats by winning margin and turnout. The trend line is flat. Why aren't they trying harder?

In a party-dominated system where voters have individual agency, competitive elections will have high turnout rates. Parties/candidates will address issues of concern to voters; even prompt voters by raising issues favourable to themselves and disadvantageous to rivals.

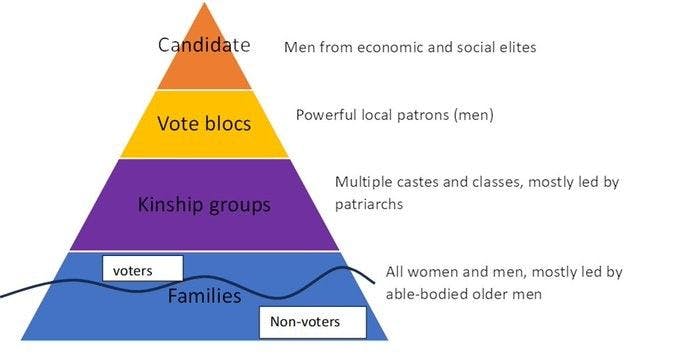

In a patronage-based system there are layers of decision-making and coalition-building between the candidate and the voter. Candidates rely on local vote bloc leaders, who in turn rely on kinship-based networks, which in turn rely on families to marshal political choices.

It is pyramidical. At the top are men from the economic elite. Not just landlords. Also those who have risen up through education, state employment, remittances, even politics - the available channels of economic mobility.

At each tier in between are men who can build coalitions in order to gain access to the level above. At the bottom are ordinary voters, women and men, members of families that are mobilised through the pyramid. There is a wider deeper base below ground - the non-voters.

Most people have some access to the top of the pyramid, which in turn has access to public resources and institutions. But access is highly mediated, almost entirely through vertical patriarchal networks. A societal structure that turns into a political machine on demand.

Within a rural context, the political machine of all candidates and parties is similar. They rely on the same social structure with some variations. It is focused on ensuring that members of the vote bloc turn out for THEM, or at least NOT turnout for the rival.

There are threats and coercion too, but the stability of the system is ensured through a series of negotiations and deals. Coercion is not just between the higher tiers and lower tiers - also within households - women may face GBV if dissent.

The political contract runs along tiers of patronage, through able-bodied male family heads. Women, younger and elderly men, and people of different ability are ‘hard to reach’ voters for which exemptions can be made as long as they don’t vote for a rival vote bloc.

In sum: Patriarchal social structure IS the 'efficient' political machine for all candidates. Women and other ‘hard to reach’ voters are marginal and dispensable.